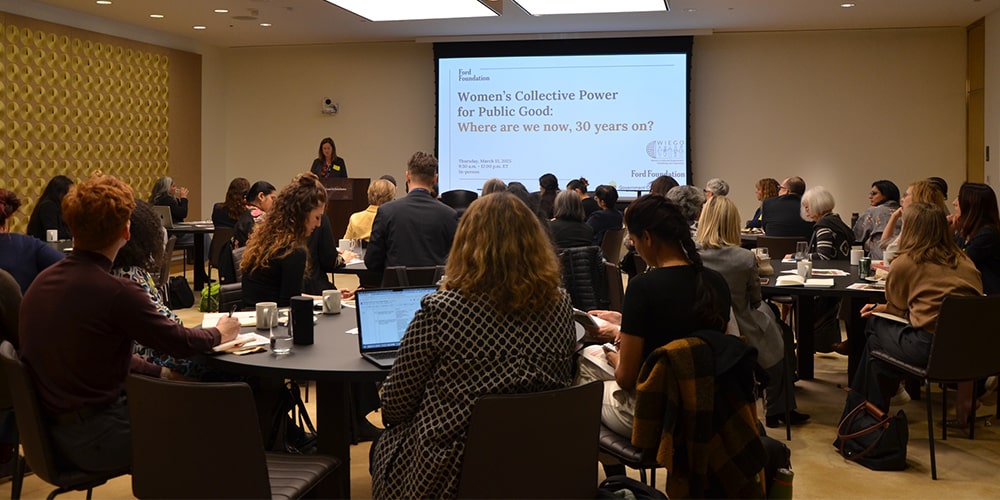

HomeNet International (HNI) participated in the panel discussion titled “Women’s Collective Power for Public Good: Where Are We Now, 30 Years On?” This event, hosted by the Government of Sweden, the Ford Foundation, and WIEGO, took place in March 2025, coinciding with the Commission on the Status of Women in New York, which was also attended by HNI.

The discussion focused on the vital role of women’s collectives in advancing women’s rights and economic empowerment, addressing critical issues such as care provision, social protection, and gender-based violence.

As CSW marked 30 years since the Beijing Conference, the session explored the significance of these groups, the challenges they face amidst various headwinds, and the need for greater recognition and support for women’s collectives. This includes legal recognition, funding, training, and representation in policy development.

Janhavi Dave, HNI International Coordinator, spoke on policy issues surrounding social protection for home-based workers. Below is a written account of her intervention:

It is true that for home-based workers, policy issues around social protection have often been distant from their immediate realities, which primarily revolve around gaining recognition as workers, accessing work, and securing minimum wages.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic changed this landscape. During the pandemic, when home-based workers faced little to no work, their top demands were access to work and social protection. They urged to be included in social protection policies. In response, HNI was asked to build the capacity of leaders for negotiating social protection, which led to the development of one of our first programs on this topic.

The COVID-19 pandemic also ushered in digital systems, prompting worker organizations to play a mediating role between these systems and the workers, as seen with initiatives like the e-Shram portal in India.

In India, social security laws have been consolidated into Social Security Codes, which present several challenges. During and especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, SEWA, along with other central trade unions, advocated for social protection for informal economy workers, emphasizing the need for easier access. This advocacy resulted in the government creating the e-Shram portal to register and collect data on informal or unorganized workers. While the intent was commendable, many workers, particularly those with limited digital literacy, found it difficult to register on this online portal. Furthermore, home-based workers were initially excluded from the list of recognized worker categories. Through multiple meetings with the government, trades of home-based workers, such as garment workers, bidi workers, incense stick makers, kite makers, alongside street vendors, construction workers, domestic workers, and agricultural workers, were eventually included.

SEWA continues to conduct digital literacy classes for its members and has organized e-Shram registration camps at workplaces, such as street vending markets, construction sites, and low-income housing communities, where home-based workers both work and live.

Today, there are approximately 500,000 SEWA members registered under the e-Shram portal, benefiting from social protection measures such as pensions, health insurance, and accident insurance. While this government initiative poses numerous challenges, SEWA remains committed to advocating for social protection and mobilizing workers on this critical issue.

There is a misconception that the move to digital systems means fewer humans are needed in the social protection process; however, this experience demonstrates the essential role of worker organizations in bridging the gap between grassroots needs and the system.

In conclusion, post-pandemic, social protection has taken center stage for home-based workers, who are pushing for inclusion in and the expansion of social protection policies at the national level, and we are working to bridge any gaps as needed.